TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Security has always been one of the most critical aspects of modern software systems. As organizations adopt microservices, Kubernetes has become the backbone of modern infrastructure for them. It orchestrates containers at scale and powers critical workloads, which means its security directly affects the stability and trustworthiness of entire applications.

But Kubernetes security can feel overwhelming. There are many layers to consider: authentication and authorization for the API server, secure communication between components, pod-level restrictions, network isolation, data protection, runtime choices and ongoing auditing. Without a clear structure it is easy to get lost in the details.

While preparing for the CNCF Certified Kubernetes Security Specialist (CKS) exam I found myself learning a lot but also struggling to connect the dots. This article is my attempt to put it all together: to organize the key aspects of Kubernetes security, highlight what matters most and present it in a way that helps both infrastructure engineers and developers build more secure clusters.

Kubernetes Cluster Components

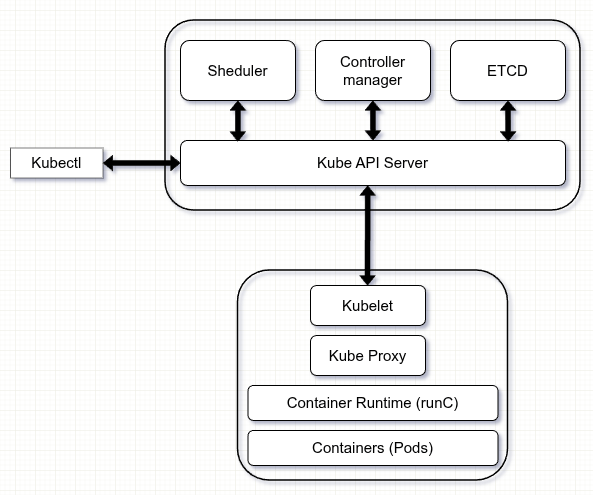

Before looking at security it helps to recall how Kubernetes itself is structured.

At the center of every Kubernetes cluster is the control plane, which manages the overall state of the system. The key components of the control plane are the Kube API Server, which serves as the entry point for every request from users and internal components; ETCD, a distributed key-value store where Kubernetes keeps all its configuration and state data; the Scheduler, which decides on which node each new pod should run and the Controller Manager, which operates background controllers responsible for tasks such as scaling, node management and endpoint updates.

On each worker node runs the Kubelet, an agent that communicates with the API server, executes containers and reports their status back to the control plane. Pods themselves are started by a Container runtime such as containerd or CRI-O, while network connectivity between pods is established by a CNI plugin.

Access Control in Kubernetes

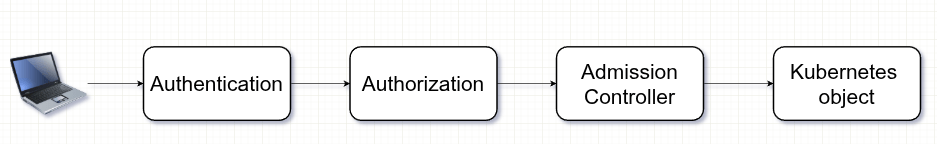

The Kube API Server is the central entry point to the cluster. Every interaction, whether from administrators, developers or internal components, goes through the API server. Because of this, access control is one of the most important layers of Kubernetes security. It can be broken down into three main stages: authentication, authorization and admission control, so every request to the Kubernetes API passes through these three phases accordingly.

Authentication

The first step in Kubernetes access control is authentication, which verifies who is making a request to the API server.

Users and Identity Services

Human users are typically managed outside of Kubernetes. They authenticate using methods such as client certificates, bearer tokens or through integration with external identity providers like OIDC (OpenID Connect) or LDAP. For example, a developer might log in via an enterprise identity provider (Okta, Keycloak) and then receive credentials that Kubernetes accepts. This model keeps user management centralized and consistent across systems.

Service Accounts

While human users are external, workloads running inside the cluster need their own identities. For this purpose Kubernetes provides Service Accounts. A service account is a special type of account created and managed within the cluster. Pods can use a service account to authenticate to the API server and perform actions on resources. By default, each namespace has a default service account, but best practice is to create dedicated ones with specific permissions.

Certificates and Tokens

Authentication in Kubernetes is usually based on strong cryptographic credentials.

- x.509 certificates are widely used for components such as kubelets, administrators or API-to-etcd communication. Certificates are signed by the cluster’s certificate authority (CA) to ensure trust.

- Tokens (like JSON Web Tokens, or JWTs) are often used by service accounts. Pods receive tokens mounted into their filesystem, which they can use to call the API server securely.

Authentication in Kubernetes is about proving identity, not permissions. Users are verified through external systems, workloads authenticate with service accounts and both rely on certificates and tokens to establish trust with the API server. Once a request is authenticated, Kubernetes moves on to the next step.

Authorization

Once a request is authenticated, Kubernetes must decide whether the user or service account is allowed to perform the action. This step is called authorization. Kubernetes supports several authorization modes, each designed for different purposes.

The most common mechanism is Role-Based Access Control (RBAC). With RBAC permissions are grouped into roles which are then bound to users or service accounts through role bindings. This approach provides fine-grained control and has become the standard way to manage access in Kubernetes clusters.

An older option is Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC). In this model policies are defined based on attributes of the request such as the user, resource or action. While flexible it is rarely used today because RBAC offers a simpler and more manageable model.

Kubernetes also includes a special Node Authorizer for kubelets. Kubelets need to access the API server to read information about services, endpoints, nodes and pods, and they also report back with node status. Requests from kubelets are identified by a naming convention (system:node:<nodeName>) and grouped under system:nodes. The Node Authorizer grants these kubelets only the permissions they need to perform their duties and nothing more.

Finally there is the Webhook Authorizer which allows delegating authorization decisions to an external service. This is useful when organizations need to enforce custom or centralized policies that go beyond what RBAC provides.

These authorization modes define exactly which actions an authenticated identity can take inside the cluster.

Admission Controllers

Even after a request is authenticated and authorized Kubernetes may still enforce additional rules before it stores objects in etcd or applies changes in the cluster. This extra layer of checks is handled by admission controllers.

Admission controllers are plugins that act like gatekeepers for the API server. Every API request that passes authentication and authorization flows through them. At this point the request is already coming from a trusted identity, it permitted by RBAC or another authorizer, but admission controllers can still evaluate whether the request follows cluster policies. They can deny the request entirely or modify it before it is persisted.

There are two categories of admission controllers. Validating admission controllers evaluate incoming requests against rules and either allow or reject them. For example, they can enforce that every pod must have specific labels or that only certain storage classes are permitted. Mutating admission controllers go one step further: they can change requests on the fly. For instance they can automatically inject a sidecar container into pods or add default values to fields that were left empty.

Together authentication, authorization and admission control form the first and most important security perimeter in Kubernetes. Authentication proves who is making the request, authorization decides what that identity is allowed to do and admission controllers enforce detailed policies about how the cluster should be used. This layered approach protects the API server and governs all interactions with the cluster.

Secure Communication Inside the Cluster

Kubernetes is a distributed system, which means its components on both the control plane and the worker nodes constantly talk to each other. The Kube API Server communicates with ETCD, the Controller Manager, the Scheduler and every kubelet in the cluster. To prevent eavesdropping or tampering almost all of these connections are secured with TLS.

The communication between the Kube API server and ETCD is always encrypted with TLS and ETCD requires valid client certificates before it accepts any connection. This layer of protection is critical because ETCD holds the entire state of the cluster including sensitive information such as secrets. The Kube API server also communicates with kubelets using HTTPS, while kubelets authenticate to the Kube API server with client certificates. Even the internal control plane components like the scheduler and the controller manager connect to the API server through TLS-secured endpoints, ensuring that every critical pathway is encrypted and trusted.

Because certificates form the foundation of this trust model, certificate management is an essential security concern. Kubernetes relies on x.509 certificates that are typically signed by a cluster certificate authority (CA). These certificates have expiration dates, and if they are not rotated properly, an expired certificate can cause disruption and outages. To address this, Kubernetes provides built-in certificate rotation for kubelets and also supports rotation for service account tokens using projected service account tokens.

TLS and certificates are the backbone of Kubernetes security. Without properly encrypted connections and carefully managed certificates, other security mechanisms lose their value because attackers could intercept traffic or impersonate components. In a distributed system where every part depends on secure communication, protecting the channels between components is as important as protecting the workloads themselves.

Secrets Data Security

As it was already mentioned in this article, Kubernetes stores all of its state in ETCD, including sensitive objects such as Secrets. By default these secrets are only base64-encoded, which means they are stored in ETCD in plain text and can be read by anyone with access to the database or to a backup. To address this risk Kubernetes supports encryption at rest. With this feature enabled secrets are encrypted before they are written to ETCD and only decrypted when accessed through the Kube API server.

Encryption at rest is configured through an encryption provider defined in the Kube API server configuration. The provider specifies which resources should be encrypted, which algorithm should be used and what key material is applied. Kubernetes supports several providers including AES-CBC, AES-GCM and KMS plugins that delegate encryption to external key management services. Once enabled every new secret is stored encrypted and existing secrets can be re-encrypted with a simple rotation process.

Enabling secret encryption is an important step for hardening any Kubernetes cluster. It ensures that even if ETCD snapshots or backups are exposed, the most sensitive data remains protected and unreadable without access to the encryption keys.

See the next part Security in Kubernetes – Part 2

By Pavel Luksha, Senior DevOps Engineer, Klika Tech, Inc.