Pod-level Security

In the kubernetes world pods are the basic units that run applications. This makes them one of the most important layers to secure. If pods are misconfigured or left unrestricted they can become an easy entry point for attackers or allow applications to gain more privileges than intended. Kubernetes provides several mechanisms to define and enforce what a pod and its containers are permitted to do, reducing risks and keeping workloads isolated.

SecurityContext Basics

Every pod and every container in Kubernetes can be configured with a securityContext. This is a set of parameters that defines how the containerized process interacts with the underlying operating system. In simple terms it tells Kubernetes which privileges the container is allowed to have and which restrictions must be applied.

Privileges in this context mean the rights a process has when running inside a container. At the operating system level a container is nothing more than a Linux process that is isolated with namespaces and controlled with cgroups. By default, the root user inside a container still maps to root on the host kernel, which means it can potentially perform powerful operations such as loading kernel modules, changing system settings or accessing hardware devices. This is a major risk in multi-tenant environments because a breakout from a container running as root could compromise the entire node.

Restrictions are the opposite to privileges. They define the limits on what a containerized process can do, such as preventing it from writing to the root filesystem, forcing it to run as a non-root user or blocking privilege escalation. Kubernetes exposes many of these restrictions through the securityContext, but underneath it relies heavily on Linux Security Modules.

The kernel provides several mechanisms to enforce restrictions: AppArmor applies security profiles that specify which files and system resources a process may access, effectively creating a whitelist of allowed operations. Seccomp operates at the system call level, filtering which kernel calls a process can make and preventing dangerous ones like mount or ptrace unless explicitly allowed. Linux capabilities go a step further by breaking the all-powerful root privileges into fine-grained units. For example NET_ADMIN allows control over network interfaces and routing tables, while SYS_TIME allows modification of the system clock. By carefully granting only the necessary capabilities and dropping the rest, administrators can significantly reduce the attack surface of a container.

Together, restrictions applied via the securityContext and enforced by kernel features like AppArmor, seccomp and capabilities allow Kubernetes to apply the principle of least privilege at the process level. Instead of treating root as an all-or-nothing role, they provide flexible and layered defenses that make it much harder for an attacker to abuse compromised workloads.

Pod Security Standards and PSA Controllers

While securityContext settings and Linux Security Modules provide strong security controls, they operate at the level of individual pods and containers. In large clusters with hundreds of workloads it becomes unrealistic to rely on every team manually setting the right values. This is where Pod Security Standards (PSS) and the Pod Security Admission (PSA) controller come into play.

Pod Security Standards define three graduated policy levels that describe how restrictive a pod configuration should be. The Privileged level is the least restrictive and permits almost any configuration, making it suitable only for trusted system workloads. The Baseline level blocks known risky practices such as running privileged containers or using host namespaces but still allows most common application deployments. The Restricted level enforces the most stringent rules, requiring pods to run as non-root, drop unnecessary capabilities and mount filesystems as read-only wherever possible.

The Pod Security Admission controller is a built-in Kubernetes mechanism that enforces these standards automatically. It evaluates every incoming pod specification and decides whether to admit, reject or warn based on the selected standard for that namespace. For example, a namespace configured with the Restricted policy will reject any pod that attempts to run as root or requests host-level privileges, regardless of what is defined in its securityContext.

Network-level security

Kubernetes networking is open by default, i.e. any pod can talk to any other pod across the cluster. While this makes development easy, it creates a serious security risk in production. Network policies are the primary mechanism to restrict pod-to-pod communication.

Network Policies

A native Kubernetes network policy defines how pods are allowed to communicate with each other and with external endpoints. One of the most important practices is to create a default deny policy that matches all pods but allows no ingress or egress traffic. This enforces a “deny by default” posture, after which only the explicitly permitted flows are allowed. Network policies can also be based on namespace selectors that restrict or allow traffic between entire namespaces, which is particularly useful for isolating environments such as development and production. For even more fine-grained control, pod selectors can be used so that only specific pods, usually identified by labels, are able to talk to one another.

vim NetworkPolicy.yaml

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: test-network-policy

namespace: default

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

role: db

policyTypes:

- Ingress

- Egress

ingress:

- from:

- ipBlock:

cidr: 172.17.0.0/16

except:

- 172.17.1.0/24

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

project: myproject

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

role: frontend

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 6379

egress:

- to:

- ipBlock:

cidr: 10.0.0.0/24

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 5978By using network policies in this way you can isolate applications, enforce the principle of least privilege and significantly reduce the blast radius in the event that a pod is compromised.

Advanced Options with Cilium

While native Kubernetes network policies cover the fundamentals of pod-to-pod and namespace-level communication, some CNI plugins extend these capabilities further. One of the most advanced is Cilium. Unlike standard policies that stop at the IP and port layer, Cilium can enforce rules at the application layer. This allows you to control traffic based on protocol-specific attributes, such as permitting only certain HTTP methods or gRPC calls. Cilium also introduces DNS-aware policies that filter outbound connections by domain names, helping prevent compromised pods from sending data to untrusted or unknown hosts.

By combining the basic protections of Kubernetes network policies with the advanced features provided by plugins like Cilium, a cluster can be transformed from a flat and insecure network into a segmented and controlled environment where every flow of traffic is explicit, intentional and auditable.

Runtime and Sandbox Runtime

Container Runtimes

Kubernetes itself does not run containers directly. Instead, it delegates this task to container runtimes – a software which is responsible for creating, starting and managing containers on each node. This abstraction allows Kubernetes to support multiple runtime implementations.

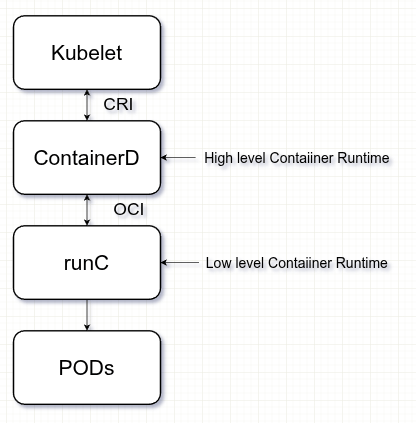

The kubelet, the agent running on every node, interacts with the runtime through the Container Runtime Interface (CRI). The CRI is a gRPC-based API that standardizes how Kubernetes communicates with container runtimes. Thanks to CRI, the kubelet does not need to know the internal details of Docker, containerd or CRI-O, it just simply issues CRI calls, and the runtime translates those into actual container operations.

In the diagram, the ContainerD component represents a high-level container runtime. ContainerD is lightweight and designed specifically for Kubernetes. It implements the CRI, receives instructions from the kubelet and manages container images, storage and networking. However, ContainerD itself does not create containers directly. Instead, it delegates that task to a low-level container runtime.

The low-level runtime most commonly used is runC, which is the reference implementation of the Open Container Initiative (OCI) runtime specification. The OCI was established to standardize how containers are defined and run across different systems. It defines two key specifications: the runtime spec, which describes how to run a container, and the image spec, which defines how container images are packaged. RunC follows the runtime spec to launch containers based on OCI-compliant images.

Putting it all together, the kubelet talks to ContainerD over the CRI, ContainerD uses runC to start containers following the OCI runtime spec, and the containers themselves are assembled from images that follow the OCI image spec.

Sandboxes and When to Use Them

The layered runtime architecture built around CRI and OCI ensures flexibility. Kubernetes can use different high-level runtimes like CRI-O or Containerd, and it can swap low-level runtimes as long as they conform to the OCI runtime specification. In most cases clusters rely on runC, which is lightweight and efficient, but it depends entirely on the host kernel for isolation. This works well for standard applications, yet it also means that if the host kernel is exploited the boundary between workloads can collapse.

To address these scenarios the kubernetes ecosystem offers sandboxed runtimes that provide stronger isolation. gVisor, developed by Google, is one example. It implements a user-space kernel that intercepts and validates system calls before they reach the host kernel, dramatically shrinking the attack surface.

# cat RuntimeClassy.yaml

# RuntimeClass is defined in the node.k8s.io API group

apiVersion: node.k8s.io/v1

kind: RuntimeClass

metadata:

# The name the RuntimeClass will be referenced by.

# RuntimeClass is a non-namespaced resource.

name: gvisor

# The name of the corresponding CRI configuration

handler: runsc Sandboxed runtimes are especially valuable when workloads cannot fully trust each other. A platform that executes user-submitted code, a SaaS product hosting multiple customer environments on the same cluster or sensitive applications that must be isolated from the rest of the system all benefit from these stronger runtime boundaries.

Ultimately, choosing the right runtime is always a balance between performance, density and security. For most clusters runC strikes the right balance, but when strict separation is required runtimes like gVisor provide an additional layer of defense that significantly reduces the risks of container breakout or kernel exploitation.

Security auditing and scanning

Even with strong configurations in place, security is never a one-time setup. Kubernetes clusters are dynamic systems where workloads change frequently, new images are deployed daily and the underlying software continues to evolve. This means that clusters and workloads must be continuously observed and audited to ensure that best practices are being followed and that vulnerabilities are discovered before they can be exploited.

Kube API auditing

One of the most powerful features for security observability in Kubernetes is the API audit log. Since every interaction with the cluster passes through the Kube API server, auditing at this level provides a complete trail of who did what and when. The audit log answers fundamental questions such as what happened, when did it happen, who initiated it, on what resource did it occur, where was it observed, from where was it initiated and to where was it directed. For example, the audit log can reveal that a particular user modified a ConfigMap at a specific time from a given IP address using a certain authentication method.

In addition to native auditing, runtime security tools like Falco extend observability beyond the API. Falco operates at the kernel level, monitoring system calls made by containers and detecting abnormal behavior. While audit logs show you what was requested through the API, Falco shows you what actually happens inside running workloads. Together they provide complementary views: the audit log answers “who asked Kubernetes to do something,” while Falco answers “what the container really did.”

Kube-bench

One widely used tool for auditing is kube-bench, which checks a cluster against the CIS Kubernetes Benchmark. It runs automated tests to detect insecure configurations such as overly permissive API server flags, missing audit logging or misconfigured kubelet options. Regularly running kube-bench helps administrators maintain a baseline level of compliance and catch regressions as clusters are upgraded.

Container Image Security

Another important aspect of auditing is container image security. Because Kubernetes relies entirely on container images to deliver workloads, insecure images can undermine all other layers of defense. Following Dockerfile best practices, such as using minimal base images, avoiding root users and removing unnecessary packages, reduces the attack surface. On top of that, images should be scanned for known vulnerabilities with tools like Trivy or the built-in scanners provided by registries such as Amazon ECR. Continuous scanning ensures that outdated libraries and CVEs are identified quickly and can be patched through regular rebuilds.

Security auditing and scanning act as the safety net of Kubernetes security. They provide continuous feedback, highlight weak points and help ensure that insecure configurations or vulnerable images do not silently slip into production.

Conclusion

Kubernetes security is best understood as a series of layers, each building on the next to protect the cluster as a whole. At the front sits the API server, the central entry point that must be guarded with strong authentication, clear authorization policies and strict admission control. From there the focus shifts to communication security, where TLS and proper certificate management ensure that every component in this distributed system can trust the others.

At the workload level pods and containers require careful restrictions through securityContext and Pod Security Standards so that applications run with the least privilege necessary. Beyond the pod boundary, network policies enforce segmentation and control traffic flow, with advanced plugins like Cilium adding application-level and DNS-based controls.

Cluster data must also be protected. Secrets in etcd should never remain in plain text, and enabling encryption at rest with proper key management ensures that sensitive information is safeguarded even in backups or snapshots. At the same time, the runtime layer defines how workloads are executed. Runc provides the default isolation, but sandboxed runtimes like gVisor can create much stronger boundaries for untrusted or multi-tenant environments.

Finally, security does not end with configuration. Continuous auditing and scanning with tools like kube-bench, along with image vulnerability scanning and host hardening, provide the feedback loop to catch misconfigurations and risks before they reach production.

Taken together these layers form a defense-in-depth strategy for Kubernetes. No single mechanism is enough on its own, but by aligning API security, encrypted communications, pod restrictions, network isolation, data protection, runtime choice and continuous auditing you create a resilient and trustworthy foundation for running applications at scale.

See the previous part Security in Kubernetes – Part 1

By Pavel Luksha, Senior DevOps Engineer, Klika Tech, Inc.